The coronavirus pandemic is going to have short- and mid-term impacts on the fan experience at stadiums. An enforced social-distancing policy by its very nature will likely lead to fewer people allowed in stadiums and arenas when sports return in earnest. And it remains unclear what if any long-term impact there may be on seating at these venues as the result of the need for people to separate for their health.

But even before the pandemic forced venue operators to think about such measures, the trend was already in place to reduce the footprint at sports venues—an effort to downsize to increase the quality of the fan experience. With teams—when they are able to have fans again—increasingly focused on activation spaces, smaller capacities are a trade-off nearly every team seems willing to make knowing those who do attend will have a better seat than ever before.

“Everywhere in baseball, it seems like the footprint has gone down a bit,” said Sean Decker, executive vice president of sports and entertainment for the Texas Rangers. “I certainly think there is a desire to create a more intimate atmosphere with premium hospitality and great fan experience you can deliver.”

Sponsored Content

Take Me Out to the Ballgame

Major League Baseball has particularly embraced the philosophy of downsizing stadiums over the past two decades, as seven new or renovated venues online since 2000 have a combined lower capacity of over 65,000 seats.

Citi Field, the New York Mets’ home since 2009, has 15,411 fewer seats than Shea Stadium. The home stadiums for the New York Yankees, Minnesota Twins, Florida Marlins and Atlanta Braves each have at least 8,000 fewer seats than their previous homes. When the Tampa Bay Rays opened Tropicana Field in 1998, the capacity was 43,369; should the Rays be able to have home games this season, capacity will shrink to 25,000 even before social distancing was a consideration.

“The sizes start to shrink because they’re trying to right-size the market,” said Christopher Lamberth, principal in the tvsdesign public assembly practice. “You get that increased intimacy.”

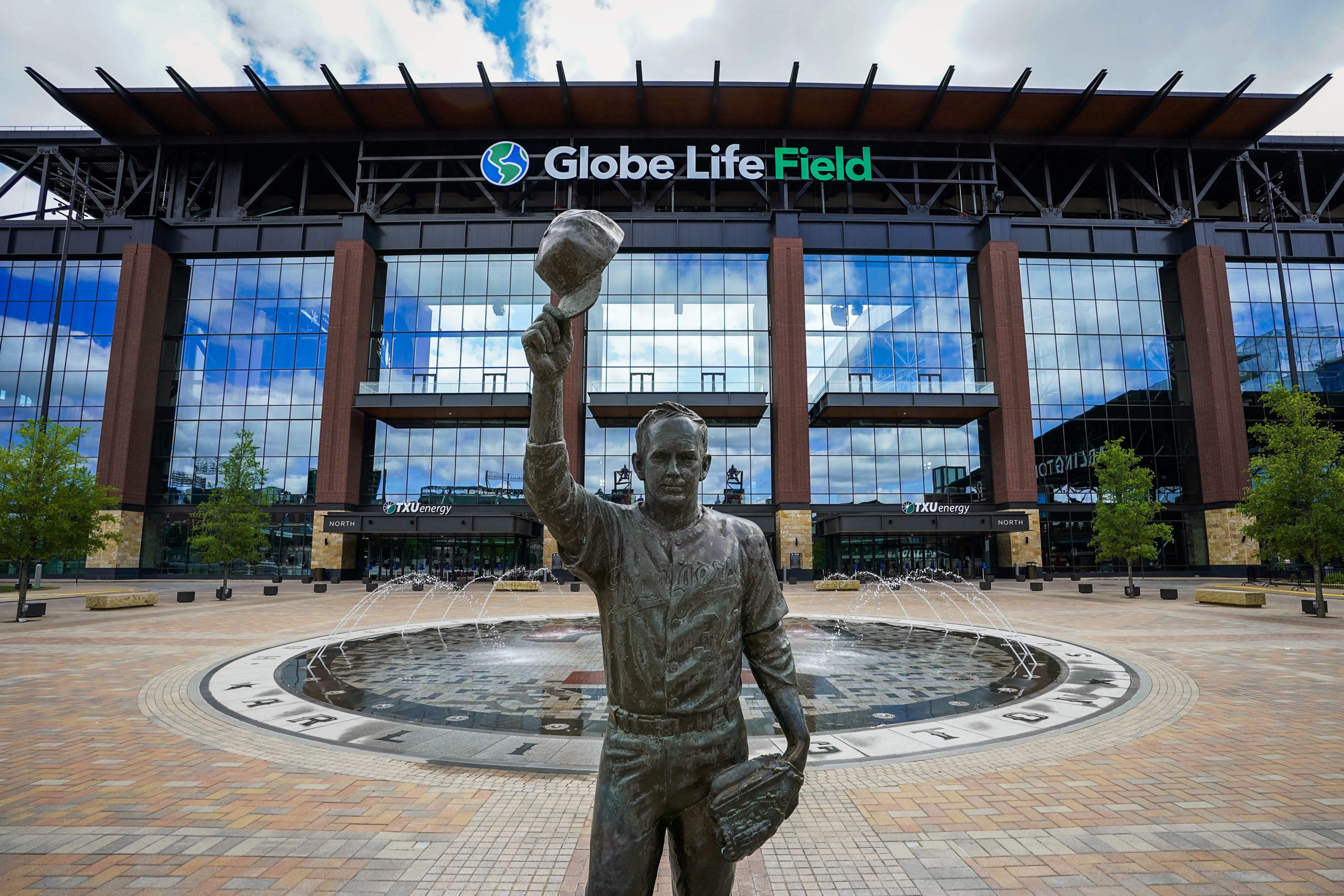

Before the coronavirus stopped baseball season before it could begin, Globe Life Field in Arlington, Texas, was poised to be the sport’s newest venue. The home of the Texas Rangers will have a capacity of 40,300, a downsizing of 21% from its previous home.

Decker said although the Rangers’ old venue would be full for opening day or big promotions, “40,000 seemed a more palatable number on a regular basis.” Yet while it has a smaller capacity, Globe Life Field has a 28% larger overall footprint with increased space between rows for fans to maneuver and each seat widened two inches for comfort — moves which, upon reflection, take on added emphasis in a post-coronavirus world.

“The focus is not nearly much now as to how many people we can get to the building, but how great an experience we can give people once they get in the building,” Decker said during an interview in February.

Driving experiences for fans with more activations, said Ryan Sickman, sports and convention centers leader and principal at Gensler, is why when teams decide to do a stadium renovation rather than a new build, the result is a lower capacity within the existing footprint.

“It doesn’t matter how large the venue is if the experiences offered in the venue aren’t what people want,” Sickman said. “We saw this in the collegiate football market about five, six years ago with a decline in student attendance. Since then a lot of schools have offered up different experiences to get people to stadiums.”

“That’s kind of the crux of where we are with design right now,” added Byron Chambers, principal at Populous and design director of the firm’s Dallas office. “The idea 25 years ago where you may have 50,000 seats and the way the revenue models work with revenue sharing and the competition for the entertainment dollar — it’s not about getting a bunch of people to the game, it’s about having a custom tailored experience while they’re there.”

A feeding frenzy

For nearly as long as there has been baseball, there has been ballpark food. It is an integral part of the sport, from the proverbial Dodger dog to singing about peanuts and cracker jack in ‘Take Me Out to the Ballgame.’

The entire concept of concessions will change in a post-coronavirus world, whether it be limited options or how orders will be delivered to fans. No matter how it changes — and it undoubtedly will — it also cannot be denied that baseball has always embraced food in unique ways.

“There is a much greater eye today on food and beverages,” said Decker. “We have our own pastry chef and do all our desserts in-house. I don’t think anybody would have considered that 25 years ago.”

While it feels longer than a year ago, it was 2019 when MLB FoodFest was held in Los Angeles and New York City with samples from stadium menus — the Los Angeles event proved so popular, tickets were sold in two-hour time limits to prevent overcrowding at the venue. The Rangers’ offering was a mustard-smothered corn dog with a dill pickle wrapped around the hot dog, which was entirely gluttonous — nobody asked and it was probably better left unsaid what the calorie count was — but also delicious.

“It’s no longer a hot dog and soda or beer,” Decker said. “People are looking for a whole different culinary experience.”

And is that ability for fans to get high-class menu options — whenever made available again — is one way for teams to get additional revenue.

“The idea of the premium food offering has gone up,” Lamberth said. “There’s always been a stadium club, but the quantities and locations have changed. Some of them can be micro-brew locations, things you’re now seeing with spirits and liquor or whiskey bar or tequila bar. … The idea of a food court is out there now with the food hall culture and how you can bring that to stadiums in smaller amounts. You’re not necessarily buying a steak, but you have a sliced sirloin sandwich offering.”

Attracting more with less

When fans return to sports with social distancing protocols expected to limit the number of attendees, the result will be a shrinking in the ticket marketplace— and “demand is always going to drive up interest in being a part of an exclusive experience,” Sickman said.

Even when fans are allowed to fill every seat, the Oakland Athletics’ proposed future home leans into the philosophy of exclusivity. The team plays in the Oakland Coliseum, which opened in 1966 and seats over 63,000. The Athletics currently limit the capacity to 47,170 with the remaining seats covered by tarps, and they hope to open a 35,000-seat stadium in 2023— a perfect summation of the past and future for sports venue construction.

“If you go back to the 1960s and early 70s, and you look at multipurpose stadiums, the desire was to make one size fits all,” Chambers said. “The idea today is tailoring the experience to what a fan wants. As design progresses over the next 10 years, you’ll see this continue. Regardless of league or professional or collegiate, you’ll see them creating experiences that people want to invest in emotionally and monetarily.”

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000