Most Olympians punched their ticket to the Olympic Summer Games in Tokyo by qualifying at a trials or earning enough points at other competitions to make their team.

My ticket to Tokyo was punched alone in my Honda CR-V on a hot summer afternoon, in the parking lot of a Denver-area urgent care. That’s when I spit enough saliva into a vial to prove my negative COVID-19 status to begin the journey to Japan.

Well, that’s not entirely accurate. The process had really begun months before.

Just as Olympians spent months of training to put themselves in position to compete in Tokyo, journalists — while undergoing none of the athletic rigors required of athletes — had a lengthy process as well. Instead of hours of athletic training, that process included considerable paperwork, unanswered emails, a handful of late-night briefings and other bureaucratic roadblocks to put themselves in position to cover the event.

This is SportsTravel’s story of how we arrived in Tokyo to cover the Games.

Six Months Out

After the 2020 Games were postponed because of the pandemic, there were many unknowns about what the rescheduled 2021 Games would look like. In February, media that had previously been approved to cover the 2020 event were asked by their National Olympic Committees — the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee in our case — if they were still planning to come.

At the time, it was impossible to know what the situation would be like in July. Where I live in Colorado, vaccines were still only available to those most at risk, with estimates suggesting by “late summer” there may finally be full access to the public. Would I be able to get a vaccine by then? How widespread would the virus be at that point? Would the Games even happen? Realizing it was a risk, we decided to move ahead with our plans to be in Tokyo.

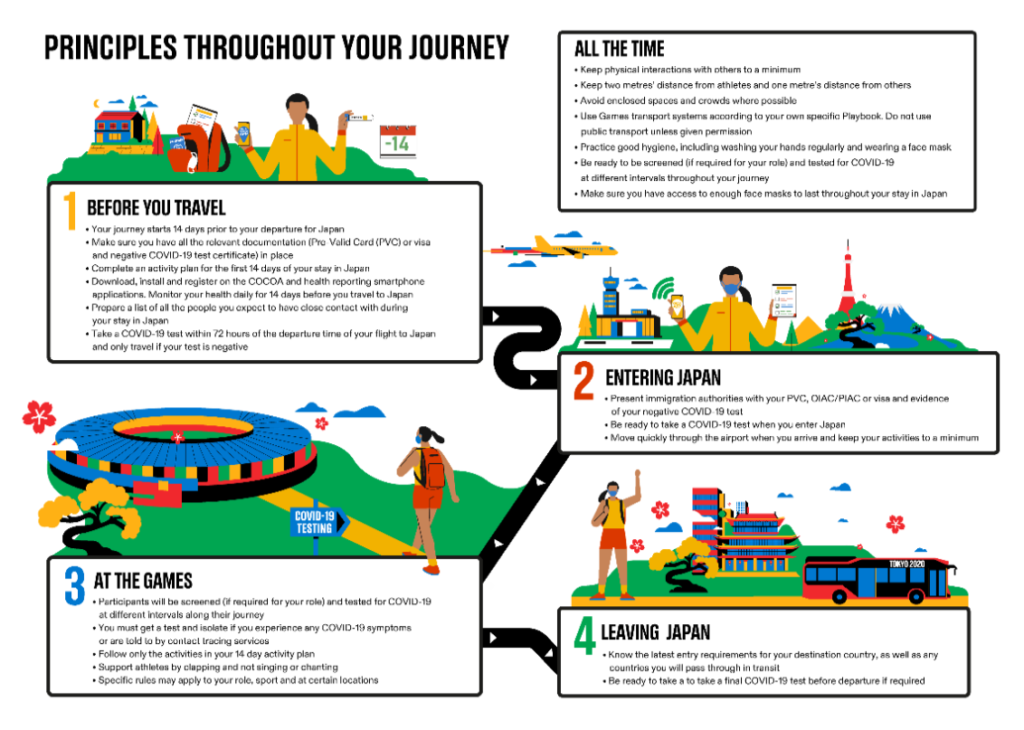

Around that same time, the International Olympic Committee issued the first of what would become three rounds of “playbooks” — multi-paged PDFs that began to outline what the expectations and experience would be for athletes, coaches, officials, international federation representatives, sponsors and journalists that make up the credentialed “Olympic Family.” Each group received its own book to cater to their specific needs.

The first of those playbooks, issued in February, was generic but laid the groundwork for what have become the rules of engagement here — regular testing both before and during your stay, limited movements only to Olympic venues or housing, an Olympics that would look nothing like normal. For the first two playbooks, the IOC held individual briefings with question-and-answer sessions for each stakeholder group. There were lots of questions on the call for media, many revolving around food. If people were not allowed to go to a restaurant as described in the book, for example, where exactly would they eat? The answer early on wasn’t entirely clear. Restaurants were off limits, we were told. But by the end of the briefing we were told we could still stop by a convenience store if we needed to get something.

While the first two playbook editions were accompanied by these (in the U.S. at least) late-night briefing sessions, the rapidly changing situation in June by the time the third playbook was issued left no time for a similar session — at a time when it felt like a briefing was never more important. The 67-page final document, the most detailed yet, would have to stand for itself. (Although on the food situation, there were at least more details, including that the Main Press Center where most journalists will work will have two restaurants and two cafes, one of which will stay open 24 hours.)

As best they could, Tokyo 2020 and the IOC had at least put the rules in place for all to see — and in some cases interpret.

One Month Out

Adherence to the playbooks, of course, is not the only requirement to get to Tokyo.

Each person participating in the Games was required to submit an Activity Plan on a provided Excel spreadsheet that asked for information such as where you will stay, for how long and where you plan to visit. There weren’t too many options on that last category as journalists were asked to stick entirely to their hotels, the press center or a competition venue. Each of the roughly 40 competition venues had its own three-digit code. If you wanted to potentially visit any of them, you had to enter all of them one by one, which is what I did on my form.

Activity Plans were due four weeks out from your arrival. To submit your plan, you had to have access to a website called ICON, an acronym for Infection Control, to upload the document. That website also was the key to unlock an app called OCHA that would later play a key role in arriving in Tokyo and monitoring your health once on site.

Tokyo 2020, the organizing committee for the Olympic Games, sent many emails about the importance of accessing the ICON website and the importance of entering your information there. But to access ICON, which was required to download the crucial OCHA app once on site, you needed an invitation from Tokyo 2020. One month from departure when my Activity Plan was supposed to be filed on ICON, I had yet to receive my invitation to log in to the site. I didn’t know what to do, although one communication I had received said to email the plan if you needed to get it to an organizer.

So, I emailed the document to Tokyo 2020 and asked for an invite to the website. When I didn’t hear back, I sent more emails. None were returned.

Two days later, there was a different issue to address. In 2020, there were dozens of hotels across Tokyo that were available for journalists to select to stay at the Games. The original plan had been for all involved to use Tokyo’s vast public transportation to get wherever you needed to go, thus a citywide housing plan. Your credential would essentially serve as your ticket on any train or bus. But the pandemic changed those plans, causing organizers to adopt a more robust busing system to keep people off public transportation and in something of a bubble.

For me, that resulted in a change of hotels about a month out of the Games at the request of Tokyo 2020. My original hotel didn’t have many journalists staying there, organizers said, and the new bus system couldn’t adequately get me there or back to where I needed to go. The new hotel would work within the system, they said, so I was happy to change.

And to be sure, I emailed a new Activity Plan with the new hotel information since I still couldn’t access the ICON website to upload or amend the document.

Three Weeks Out

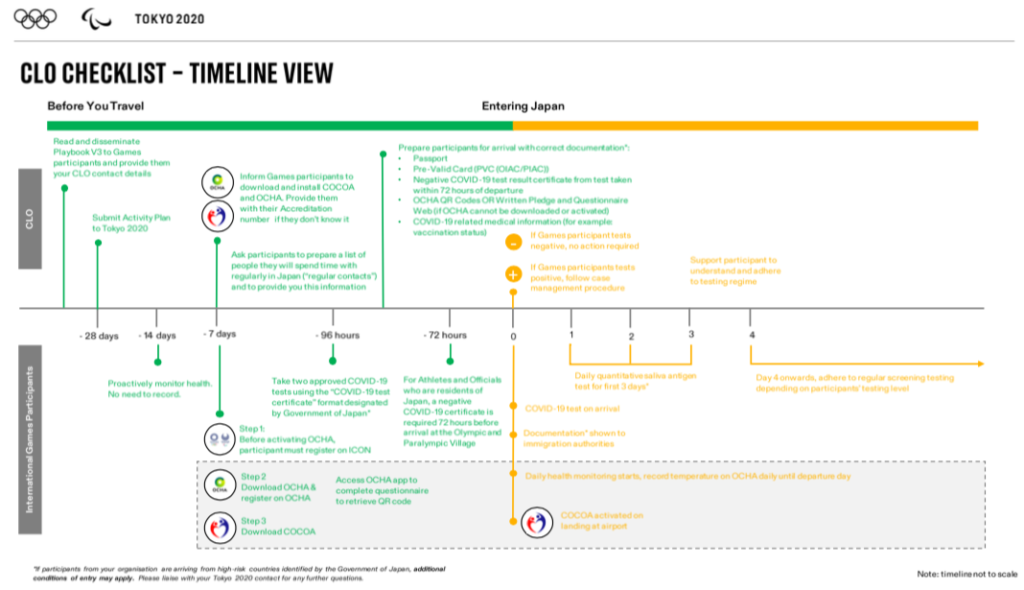

To help enforce the rules, each organization attending the Games — whether it be a sports federation or a magazine — had to assign a COVID Liaison Officer, or CLO, that would be responsible for absorbing all the information required of participants in that group. In an Olympic world that is in love with acronyms, CLO is the hot new acronym of the Tokyo Games. In the case of SportsTravel, like other organizations sending one representative, I am my own CLO.

CLOs like me were privy to a series of other emails with more multi-page PDFs explaining how often those in your group will be tested and how to order your testing kits. But after a fellow journalist who was also his own CLO forwarded me an email he had received from Tokyo 2020 in June, I realized I was not receiving these updates, which included some fairly important information such as a website to visit to place your orders for testing kits once on site.

In an Olympic world that is in love with acronyms,

CLO is the hot new acronym of the Tokyo Games.

I emailed the CLO support team in Tokyo to find out why I wasn’t on the email list. It was the first of several CLO-related emails on the topic that received only one response, which said it would take several days to reply. In the meantime, organizers said, contact my CLO to resolve any issues I might be having.

Nonetheless, within a week, I appeared to be getting emails with details, including one with five new attachments detailing more information about how testing would work. Had I not been lucky enough to find out about them from someone else, it would have been impossible to get those details.

And there were important details. All Olympics visitors had to prove two negative COVID tests within 96 hours of departure, at least one of which had to be within 72 hours of departure. That’s how I found myself at that Denver urgent care, which was identified on a spreadsheet Tokyo 2020 sent of accepted test administers. Those two tests also had to be accompanied by a signature from the doctor administering the test on a form provided by the Japanese government. Since you needed your results first, this resulted for me in a third trip to the urgent care once my two negative results were confirmed so they could sign the forms on both tests.

Once in Tokyo, depending on your role at the Olympics, you may be tested for COVID every day. There are nine different categories of Games visitors, each with their own testing schedule. Athletes are tested every day. For most journalists, in addition to the two pre-trip COVID tests and a test at the Tokyo airport upon arrival, that pattern will be tests on each of your first three days in Japan, then tests once every four days during your stay.

Meanwhile, there was also one new hang-up in accommodations. Checking the Tokyo 2020 media accommodations website (an entirely different site than ICON or any others), I noticed they had entered the length of my stay wrong in my new hotel, shorting me one day. It would take two more weeks and about 10 emails to resolve that administrative error, but eventually it was fixed.

Two Weeks Out

Two weeks out from departure, there were still several unresolved issues, the biggest of which was that I still had not received the invitation to access the ICON site. But at long last, the invite came, allowing me to officially upload my Activity Plan and download the OCHA app that would be used to monitor my health in Tokyo. That invite was accompanied by a 77-page PDF explaining how I would be able to navigate the ICON site and plan for my time in Tokyo.

I still had questions though. The 77-page PDF included mention of a website we were to use to order test kits once in Tokyo. The document included a very specific login and password to access the test site, the combination of which was declared “invalid” when you tried it. Several emails to Tokyo 2020 asking how I should handle that were never answered.

But in a few days, I did receive an email from the USOPC media staff with some details of what their own staff had experienced getting into the country. They knew Tokyo 2020 wasn’t responding very well to emails (clearly, I wasn’t the only person trying to reach them) and advised us to stay patient. That alone was reassuring in its own way.

Among the many concerns I still had: My Activity Plan had not been approved yet. Without approval you weren’t supposed

to be allowed into the country.

Among the many concerns I still had: My Activity Plan had not been approved yet. Without approval you weren’t supposed to be allowed into the country. And depending on your level of approval, you either would be allowed to operate the day after you landed if you got tested for COVID each of your first three days, or you might have to quarantine in your hotel room for three days before you could move about town. That was no small matter to me as I tried to set my agenda to cover the Games. I was hearing from other journalists who were required to stay in their rooms for three days after landing.

But there was no way to get an answer as to when the plan would be approved.

One Day Out

The morning before I was to leave, I received an email that my Activity Plan had been approved. That plan called for me to move around on Day 1, so I assumed that would be the case despite what I was hearing on the ground. I still had no resolution on how to order the test kits for when I landed, but I was resigned to figuring all that out once I got on site. I was at least able to activate the OCHA app that would be used to track my health in Japan. Key to that step was that the app now produced a QR code that would be checked multiple times in the days to come.

Knowing that I at least had my plan approved, I slept well the night before leaving, ready for whatever came up on the journey ahead.

Day of Departure

After waking up at 4:30 a.m. and leaving my house just after 5 a.m., I was at the airport in Denver in plenty of time for my 7:50 a.m. flight. When I arrived at the United counter, my check-in kiosk was flagged since I was an international traveler. When an assistant came over and found out I was going to Japan, she said, “You know they aren’t allowing any visitors there?”

Yes, but people traveling for Olympics business were being allowed in, I told her. I showed her my Olympic credential that essentially serves as a visa for Olympics visitors, but she wasn’t convinced. Surely the whole process to get this far wouldn’t fall apart at the United counter, I thought. A few nervous minutes later, all seemed to be straightened out and I boarded my first flight to San Francisco, where I would transfer for my flight to Tokyo.

At the check-in counter in San Francisco, I was asked to show that I had the QR code on the OCHA app. I also had to produce the negative test result I had taken less than 72 hours prior. My flight was about one-third full with many being Olympics travelers, including USA Swimming CEO Tim Hinchey and the entire USA Climbing team that will make its debut in Tokyo, among others.

3:00 p.m. in Tokyo

It turns out the 10-hour flight was the beginning of what would become a long and repetitive process to get out of Narita Airport in Tokyo.

When we landed, anyone traveling to another country was allowed to depart first, followed by any people staying permanently in Japan. While Olympics visitors waited for our turn, there were several new forms to fill out, including a one-page sheet that asked if you had recently had any COVID symptoms or been around anyone who had, and what country we were coming from. The United States was flagged on the sheet as a “particularly affected region.”

Eventually, the Olympics contingent — which was most of the flight — was given permission to leave.

3:40 p.m. in Tokyo

Once off the plane, we were directed to a row of chairs. Within 15 minutes, an airport employee came by to each of us to check that we had the QR code on the OHCA app. She also reviewed our passport, looked at our Olympic credential and checked our 72-hour negative result.

4:30 p.m. in Tokyo

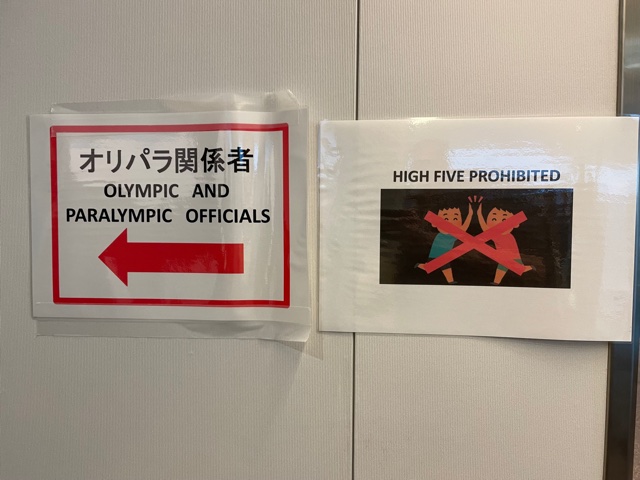

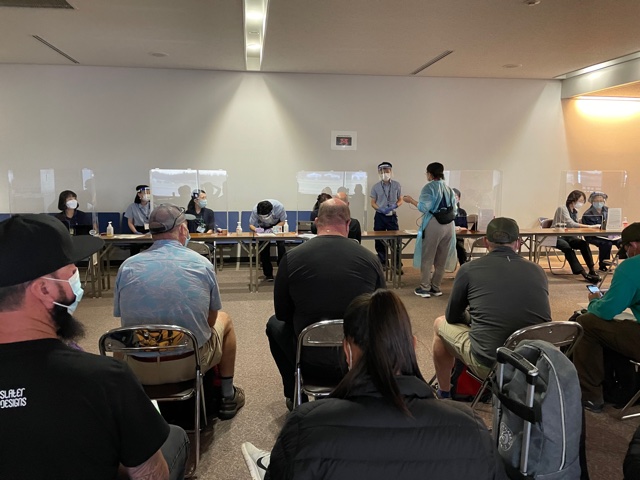

After about an hour in those chairs, we were on the move again to a new row of chairs and told to wait. In front of us, behind Plexiglass, were several stations with more people to check our forms. A sign behind them advised us that as much as we for some reason might want to engage in high-fives, they were strictly prohibited.

4:50 p.m. in Tokyo

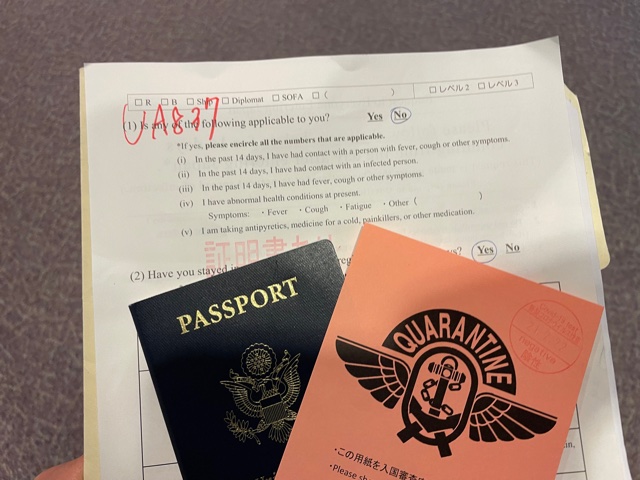

When we got to the desk, we were asked for the one-page form we had filled out on the plane, our passport and the 72-hour negative test result. At no point during any of the steps ahead was I ever asked for the 96-hour test or proof that I had taken one.

That’s when I discovered for the first time that when my urgent care doctor had stamped and signed my test results in Denver, he put the day I had taken the test but not the exact time, making it hard to pinpoint how many hours out they had been taken. This detail was of particular concern to the people behind the glass — and suddenly to me as well. Fortunately, the test result itself had the time registered on it and after a few nervous minutes, I was allowed to move to the next step.

5:05 p.m. in Tokyo

We were then sent to another line where we would wait to get our vials to take our COVID test on arrival. They checked the QR code on our OCHA app, asked for the one-page form and our passport before giving us a vial to spit into while sitting in a few chairs stationed in a room.

5:10 p.m. in Tokyo

The next stop was the ANA Lounge, which for United at Narita Airport served as the holding area while we waited for our results. There, we had to produce our passport again, which now had a sticker on the back detailing our saliva sample number. They also asked for the one-page form and assigned us a number on the form.

Once in the lounge, there were seats with numbers on the back and you went to your assigned seat that matched the new number on your form. Some lucky-numbered people received leather lounge chairs. Others like my group, which included the media representatives for USA Climbing, USA Rugby and USA Triathlon, along with two television camera operators who would work the golf event at the Games, were assigned plastic chairs.

We had plenty of time to get to know each other. I also tried to work the room, catching up with USA Swimming’s Hinchey for a story we filed later.

6:10 p.m. in Tokyo

An hour later, we still had no sign of our results. Kelly Feilke, the USA Climbing media representative, noted that his team of athletes, who were separated from us at the very first step of disembarking, had already made it to their luggage. Caryn Maconi from USA Triathlon also noted that CEO Rocky Harris had been on a different plane that landed after us and had already made it through to the luggage area as well. I tried not to be too concerned about why things were taking so long.

7:55 p.m. in Tokyo

At long last, a woman came through the lounge with a clipboard, pointing at chairs and yelling “Negative!” at each seat that she approached. When she got to our section, it was a welcome relief. It had been almost five hours since we landed.

“Let’s go Team Negative!” Feilke declared as we picked up our stuff and went to the next stop. To leave the lounge, we had to have our passport checked, our one-page form reviewed and then we received a colored pass that said “Quarantine.”

8:10 p.m. in Tokyo

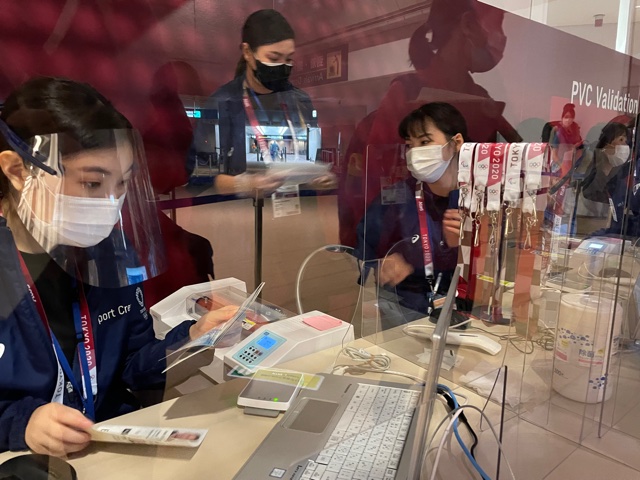

The next step was to get our Olympic credential verified. While we came to Tokyo with a piece of paper that would become our credential, it needed to be laminated and inserted with a chip that serves as an entry of sorts, along with facial ID software, to get into Olympic venues. That credential serves as the most essential document for everything you want to do during the Games.

The credentialing process was smooth and efficient and volunteers were smiling and friendly as they laminated and attached the credential to lanyards.

8:20 p.m. in Tokyo

Finally, we were on to customs, where we had our fingerprints scanned and photo taken. They checked our passports again and the QR code on our app and we were allowed to get our luggage.

8:30 p.m. in Tokyo

Luggage in hand, there was one last checkpoint, where a guard — for final good measure — checked our passport and the QR code on our app. We were then free to get transportation to our hotels.

9:00 p.m. in Tokyo

After waiting in a holding area, I boarded a bus with others in our group to a central bus station where we would be hailed a cab to our final destination.

10:00 p.m. in Tokyo

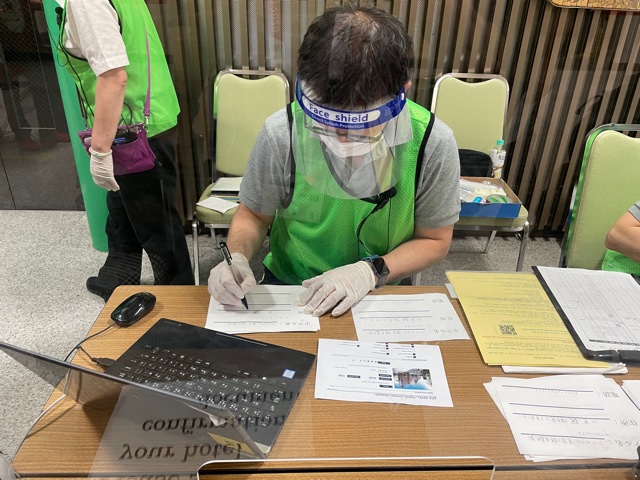

At the bus depot, there was another line you had to wait in to be processed. At this point, I was used to waiting in line.

10:30 p.m. in Tokyo

When it was my turn, I told the helpers there where my hotel was and they filled out a slip of paper in Japanese to hand to the cab driver. I was directed down an elevator to another area to wait for my cab. Only one person was allowed to take any cab for COVID countermeasures even if they were in a group together.

I was soon placed in a cab and was on my way to the hotel. Near the end of the ride, the cab driver had that universal look of being potentially lost. He tried to communicate with me about whatever his concern was but the conversation was lost in translation. Luckily, I had downloaded Google Translate and had him speak into my phone.

“Did you book this hotel yourself?” came back the translation. No, I said, Tokyo 2020 booked it for me. “It’s pretty far off the mark,” he said in translated reply. By that, I think he meant the location and not the quality of the hotel, which seems perfectly nice. In any case, we pulled up to the hotel at 10:50 p.m.

10:57 p.m. in Tokyo

After checking in, the key at long last opened the door to my small but adequate hotel room. And they had all my dates straightened away when I got there, which made me happy. From the time I left for the airport in Denver it had been a 27-hour door-to-door experience.

But it had been a longer journey than that.

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000