Sports play a vital economic role for destinations looking to attracting visitors. They also, in their finest moments, provide inspiring examples of humanity at its best.

Over the weekend of July 29–30 in Ames and Des Moines, Iowa, two events — one amateur, one professional — spoke to each of those aspects. They also served as a reminder of the importance that sports play to help cities craft an identity, to inspire people of all ages to stay active, and to encourage others to explore new parts of the world they’ve never experienced.

That was the case for me on what was my first visit to both destinations despite years of traveling for sports events. The events that eventually brought me to the Hawkeye State were the State Games of America, a massive amateur and youth event held across 30 venues mostly in Ames, and the Dew Tour, a world-class skateboarding competition at what is now the largest skatepark in the country in Des Moines.

Sponsored Content

And in the end, witnessing an incredible act of sportsmanship was the perfect capper on the best attributes that the sports-events industry have to offer.

‘Big in a Number of Ways’

I was familiar with the State Games movement from our long partnership with the National Congress of State Games, which has organized its annual symposium in conjunction with our TEAMS Conference since 2016. The State Games of America, held mostly in Ames with some events including swimming and figure skating held in downtown Des Moines, were initially planned for 2021 but were pushed back a year because of COVID-19.

This was my first experience seeing the event, in which the Iowa Games — one of the leaders in the State Games movement — took a lead role in organizing competition for visitors from 46 states, the U.S. Virgin Islands and even Canada.

The State Games of America are held biannually and are open to those who medal at their individual state games. But all participants from local states can automatically qualify, making the Iowa contingent the largest in the competition. Still, the amount of out-of-state visitation could literally be marked on the map, where participants were able to pin their hometowns for all to see at the athlete registration area inside Jack Trice Stadium on the campus of Iowa State University.

Here’s a quick look at the State Games of America by the numbers: 17,000 athletes, coaches and family members participated; 2,000 athletes came from 142 teams in soccer alone, mostly at the youth level; 600 athletes competed in track, including the oldest in the competition — an 88-year-old from Iowa — and the youngest, a boy and girl at just 4 years old. While traditional sports like soccer and track were on the schedule, so were considerably nontraditional sports like light saber and professional yoga, which allowed the Games to offer something for everyone.

The event was a coup for Ames from a destination marketing perspective, said Kevin Bourke, the president and CEO of the recently rebranded Discover Ames, whom I caught up with before the Opening Ceremony.

“It’s big in a number of ways,” Bourke said of the event. “Obviously, we want to put heads in beds, we want to bring in visitors. The thing about the State Games of America compared to the Iowa Games, is it’s not bringing in just Iowans. It’s bringing in out-of-staters. It is just so exciting to see them come here. We’re all about economic development. We’re also about trying to get people to move here ultimately. Are they? Who knows? The majority of them no. But we want them to leave with a good impression.”

The Cauldron is Lit

To that end, organizers staged a memorable Opening Ceremony at Hilton Coliseum on the campus of Iowa State with the feel of the Olympic Games, or at least as close to that experience as most competitors will ever get. It was a terrific event that featured a parade of states similar to the Olympic Games (as host state, Iowa got to march in last…), a cauldron lighting and fun and quirky facts of each state as they entered the arena. (Did you know the first traffic light in the United States was installed in Ohio? Now you know…)

The ceremony featured a keynote from Matt Stutzman, who won the World Para Archery Championships in February. Stutzman, whose hometown is Fairfield, Iowa, was born without arms and competes with his legs. His message of adapting to his circumstances and succeeding hit the perfect tone for the proceedings.

Similar to the Olympic Games, athletes, coaches and parents took an oath, pledging to compete fairly and encourage good sportsmanship. It seemed a quaint exercise but also a reminder that sometimes at the amateur and youth level, those involved need a refresher to play fair and be nice. It also seemed in line with the message of the State Games movement itself, which annually allows hundreds of thousands of everyday people the opportunity to compete in the sports they love with the best intentions.

“Kids are specializing younger and younger and the State Games movement has always been about grassroots level competition,” said Bourke, who spent over 20 years at the Iowa Games as chief operating officer before joining Discover Ames in 2019. “The first time my daughter ever competed in a golf tournament was an Iowa Games event. She was scared and she was nervous. For her to go do a Junior PGA event, she wouldn’t have done it. But the Iowa Games was less intimidating, it was more grassroots. Bringing in the State Games of America, it’s a higher level because we’re bringing in out-of-staters. But we’re raising awareness of what the Iowa Games stands for as well. Anybody can compete.”

Dew Tour Youth Movement

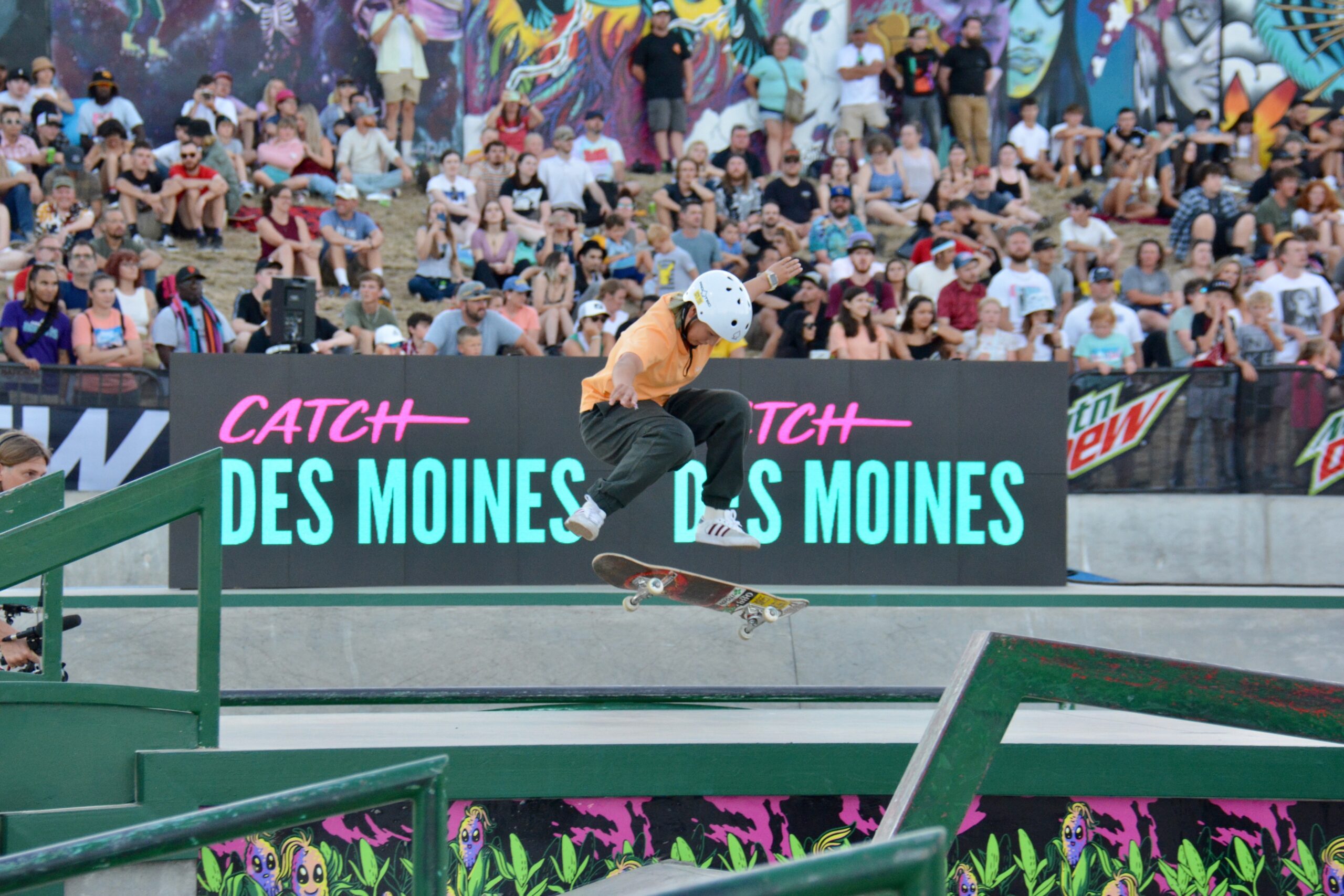

While anybody can compete in the State Games, professional skateboarding is another thing entirely. And on the other end of the sports spectrum over the same weekend was the Dew Tour at the sparkling new Lauridsen Skatepark in downtown Des Moines.

The Dew Tour may have been a professional event, but it could count as a youth sports event as well. That’s because the event’s final night of competition saw victories in women’s street by 14-year-old Momiji Nishiya from Japan (who at 13 won Olympic gold last year in Tokyo) and in men’s park by 15-year-old Gavin Bottger, an American and the youngest competitor in the discipline.

That the event was even in Des Moines is an incredible story of how investment in sports infrastructure can mean investment in destination marketing. After a 10-year effort, the Lauridsen Skatepark along the banks of the Des Moines River in downtown opened just last year. Its first event was last year’s Dew Tour, which also served as an Olympic qualifier for athletes headed to Tokyo, where skateboarding saw its Olympics debit.

The tour returned again this year after years of being in Long Beach, California, which on the surface would seem the better cultural fit. But the skatepark in Des Moines has proved that skateboarding can be a cultural fit anywhere. And the crowds that lined the course for the free-admission event (the Dew Tour reported about 24,000 attendees) were a testament to that fact, especially during a busy summer season in Des Moines.

“I’m from a small town myself and to be able to have this in the Midwest is cool. I think it’s a good blueprint for other cities to look at and see how it’s shaped the community.”

—Skater Sean Malto

I caught up with Greg Edwards, longtime president and CEO of Catch Des Moines, on the final day of competition, which saw thousands of visitors line the grassy banks of the river and participate in a robust vendor marketplace. Edwards said the park and the Dew Tour have changed the conversation about the sport locally.

“It boosts a lot of community pride,” he said. “Even folks who are not into skateboarding, they talk about it. There’s a big buzz around the community, it’s on the news channels. It’s pretty cool.”

Sports events make up 40 percent of Catch Des Moines’ group business, Edwards said, and the skatepark is now adding to that effort.

“It’s very meaningful,” he said of the event. “The leadership of the community had the vision to build this to help the community, to help the kids in the community. And with what we do bringing in events, we saw the light come on right away, and said it’s an opportunity for us to attract some new events. Skateboarding is a niche market. Not everyone’s into it. But it’s been wonderful for us, wonderful for our community, wonderful for people around the world who have finally seen Des Moines and said, ‘Wow, we had no idea corn country was this cool.’”

Athletes Notice Investment

Skateboarders have noticed as well.

“It’s definitely a random place for the biggest skatepark to be,” said Sean Malto. “But it’s a beautiful skatepark right on the river and the city is great. I’m from a small town myself and to be able to have this in the Midwest is cool. I think it’s a good blueprint for other cities to look at and see how it’s shaped the community.”

Chris Colbourn, another professional skater, noted that it’s great to have the Olympics to shoot for in addition to events like the Dew Tour. But he was astute enough to recognize that the sport’s Olympics inclusion has another potential benefit for host cities.

“It’s just cool that the Olympics now accepts skateboarding,” he said. “It paves the way for towns like Des Moines to build giant skateparks. lt’s giving the cities more reason to fund giant skateparks like this one here.”

An Act of Sportsmanship

And skateboarding itself is a wonderful reminder of how great sports can be.

The Dew Tour athletes didn’t need to take an oath to commit to good sportsmanship, although I’m sure they would have if they were asked. It is in their DNA. These are professional athletes who give their equipment out to adoring fans without any effort, as I witnessed when Steven Breeding offered his helmet to a fan after the incredible adaptive park skateboard event. (Breeding does not have a right arm.)

Following the women’s street event, when the medalists came to accept their hardware, the 14-year-old Nishiya and third place finisher — Chloe Covell, from Australia, age 12 — began playing around with each other, mocking a martial arts competition to see who could touch whom first. It was the type of behavior that just as easily could have happened with the kids on the soccer field at the State Games in Ames, and served as a reminder that these professionals are not just kids at heart, they are just kids — albeit kids who are the best in the world at what they do.

And in the men’s park competition later that night, the final run was set to determine the champion, with Olympic gold medalist Keegan Palmer (age 19) executing what to a novice fan appeared to be enough to take first place. As he stood by a monitor to see if his score would be enough to beat an earlier spectacular run by Bottger, I had my camera lens focused on Palmer to get his reaction. I was so focused on taking a shot of his winning reaction that I was pleased when he raised a triumphant fist, flashed a smile and began celebrating when the score posted.

It wasn’t until a minute later that I realized Palmer hadn’t won. He finished third despite his amazing run. His reaction was genuine — genuine excitement that his friend Bottger had beat him with a better run and won the competition.

That’s sportsmanship at its very best. And it was a perfect way to cap a weekend in Iowa that reminded me of the power that sports can have not just on the cities and venues that host them, but on the people who participate and experience them as well.

Jason Gewirtz is vice president of the Northstar Meetings Group Sports Division and executive editor and publisher of SportsTravel.

Jason Gewirtz is vice president of the Northstar Meetings Group Sports Division and executive editor and publisher of SportsTravel.

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000