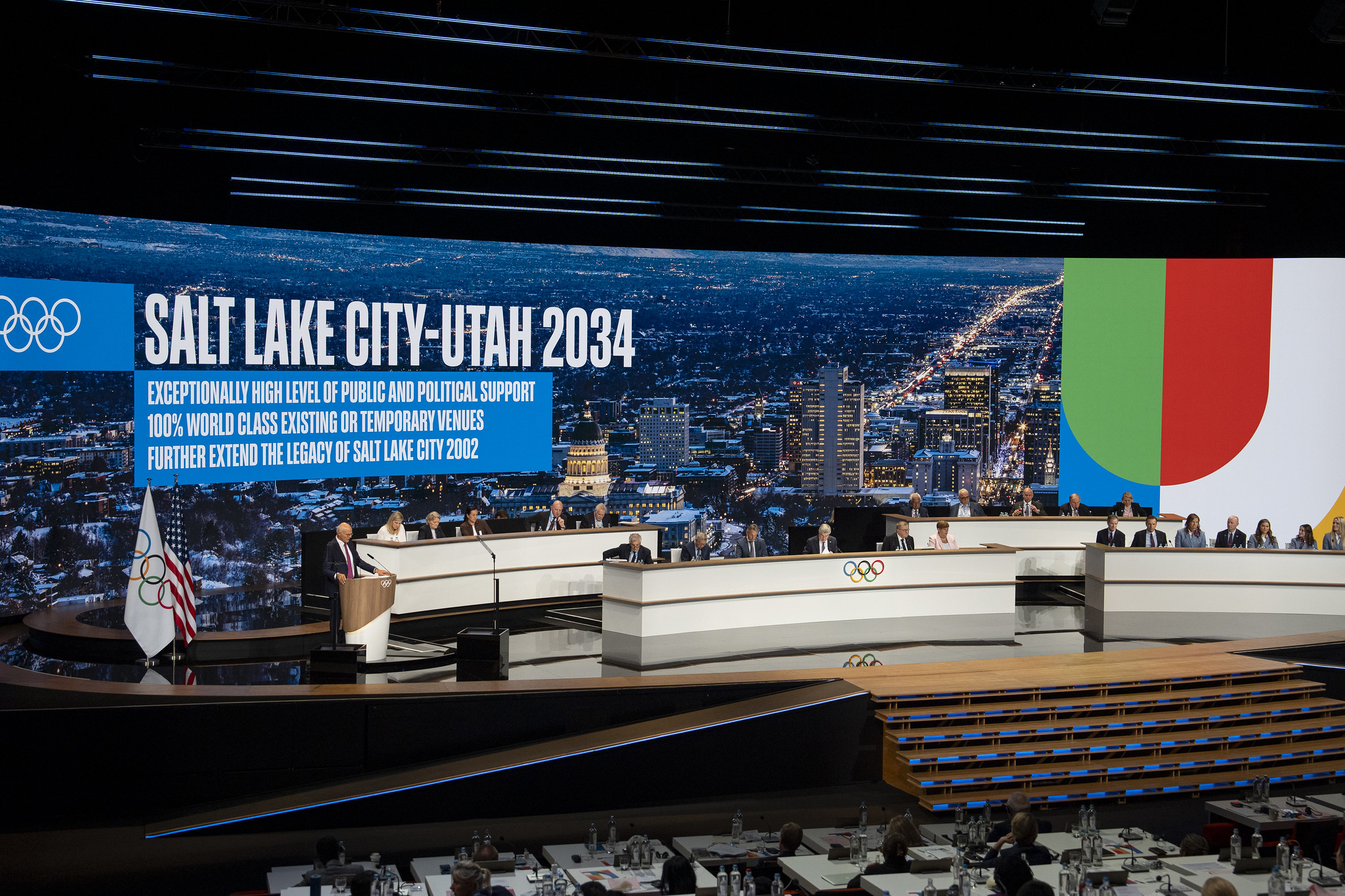

There was no need to talk about a potential host or a candidate city. IOC President Thomas Bach made the proclamation in Paris: Salt Lake City will host the 2034 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games.

City and state leaders, plus those who had shepherded the winning bid, spilled out into a mixed zone on July 24 for interviews in a daze of happiness, relief and realization that after years of speaking in abstract terms, they could talk about the Games as theirs.

“It feels like a burden has been lifted because we have the Games,” said Fraser Bullock, president and chief executive officer of the Salt Lake City-Utah Committee for the Games. “Now, a new burden comes. But this is fun, because we get to host the world and now we know it’s a real thing and we can start working toward that.”

Sponsored Content

Forward to a few months later and the third annual Sports Salt Lake Summit was held with a record number of attendees on hand, including nine national governing bodies. This winter alone, the region will host national championships in luge and speedskating plus a women’s hockey rivalry series game between the United States and Canada in addition to the multiple NGBs that already call the region home.

“The phone has been ringing,” said Clay Partain, executive director of Sports Salt Lake. “We’ve got a 10-year runway. We’ll have conversations with the national governing bodies to figure out what are the events we need, but also what are the events that we think make sense and that we both want.”

July’s awarding of the 2034 Games was a watershed moment for the region that hosted a hugely successful Games in 2002. It is in many ways the poster child for what the IOC wants from a host: venues that are maintained and used for community and high-level events for decades, boosted by a multi-million dollar surplus that has lasted nearly a generation.

The announcement came after years of negotiations, meetings and more, including atypical (some would call it manufactured) drama before the final vote of approval. SportsTravel covered the race to host the Games for years, culminating with its moment in Paris, interviews before and after the IOC Session and first-person observations from throughout the process.

This is how the 2034 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games came to Salt Lake.

The Road to Approval Begins

Returning the Games to Salt Lake has been a long-held desire. What made Bullock feel that way was his own role at the 2002 Games as chief operating officer, working with Mitt Romney in organizing an event that was once shrouded in disgrace but ended with success.

“Whether it’s within a country or between countries, there’s so much division,” Bullock said. “What’s the one thing that brings the world together in a big way? It’s the Games. The Olympics and Paralympics are unique in the world.

“I had no plans to be part of the Olympics, but Mitt pulled me in and I got a taste of it,” Bullock added. “Particularly post-9/11 where I could see a world unified, I said, OK, this is important. We all want to contribute in some way to society and this was my little niche to help.”

In Bullock, the bid also had someone who for years had built relationships with the IOC that led him to be one of Lausanne’s most trusted people within the U.S. Olympic movement.

When New York (2012) and Chicago (2016) lost in humiliating fashion in their bids to host the Summer Games, relations between the IOC and the U.S. movement were at their lowest point with acrimony over the U.S. share of Olympic television and sponsorship revenues. When the two sides in 2012 signed an agreement through 2040 after years of negotiations, Bullock was part of a three-person committee representing the USOC. And when the IOC wanted to bring in advisors to serve on committees and help organizers in Turin in 2006 … and Vancouver in 2010 … and Rio in 2016 … Bullock answered the call.

“I just wanted to just be of service to a great movement,” Bullock said. “But always in the back of my mind, I said, this is important because relationships matter. And this will be helpful in securing one element — not the element — but one of many elements to secure a future Games.”

Slowly but surely, plans became reality. The SLC-Utah Committee for the Games was formed in February 2020 with Bullock heading the group. It named Catherine Raney-Norman, a speedskater who competed in four Winter Games including 2002, as board chair in June 2021 after a meeting with the governor of Utah and mayor of Salt Lake City.

“They wanted to do a Zoom with me and I said, just so you know, I’m dressed for day care today as a mom also picking up her car at the mechanic,” Raney-Norman said with a laugh. “When they called and asked me to do this, it was an absolute yes. A moment of fear a little bit as well, knowing how important it is and the responsibility that it is, but so incredibly grateful.”

The bid group itself was fairly small, therefore taking on multiple roles depending on the duties needed.

“(Bid lead) Darren Hughes’ capabilities are 10 times greater than I even thought they were,” Bullock said. “He can do the work of 10 people. I thought I was productive, but I don’t hold a candle to Darren. Cat, I knew she was connected to the movement, but I didn’t realize how deeply connected she is with everybody at the NGBs. She knows all these athletes. She knows all these kids. She’s just a wonderful person and great to work with. And team chemistry is so important. It’s got to be the right people.”

The right people also meant knowing an Olympic bid included outreach not only to the international sports community but the local community. Local support for the bid has been remarkably strong and sustainable throughout what ended up being a years-long process.

“You have to be patient throughout the process, even though we want to go really quickly,” Raney-Norman said. “What’s really important, and I’ve so enjoyed this the last several years, is engaging with our communities and sitting down and listening to them. I can’t tell you the number of times where I would set up a meeting to go have coffee and talk about the Games in our communities and their first response was, I can’t believe the Olympic bid committee wants to talk to me. And I was like, well, why wouldn’t we?”

Debating Which Edition

As the bid gained momentum, one question kept rising — which Games would the region go for?

“I always believed the Games would come back to Utah,” Bullock said. “I just didn’t know when.”

For a long time, the bid took a neutral position, saying it would want any Games, whether it would be 2030 or 2034. Salt Lake City for a period of time was one of multiple bidders but as the process continued, others fell by the wayside.

First, there was Sapporo’s bid, which had been seen as the favorite for 2030 as an unspoken “make-good” by the IOC to Japan after the delayed 2020 Summer Games in Tokyo resulted in massive budgetary losses for the organizers. But as the Tokyo Games fallout included allegations of bribery against members of the organizing committee, Sapporo’s bid was paused and never fully revitalized.

Vancouver’s 2030 bid, the first led by the Indigenous community, was essentially ended once government funding was not secured. While Sweden weighed entering the 2030 bid process, there was a period of time in which Salt Lake seemed the only choice for the IOC.

That, however, raised complications for the IOC and USOPC because of the quick turnaround from the 2028 Summer Games in Los Angeles. There have not been consecutive Games in the same country since the 1980 Winter Games in Lake Placid followed by the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles, in part because of sponsorship and budgetary aspects given the traditional leadup a sponsor gets ahead of a Games.

Bullock’s financial budget for a 2030 Games “would be very tight,” he said, “because we would have less revenue.” So, the SLC-Utah group listened and when the USOPC publicly professed a preference for 2034, the bid was adjusted. After counsel from USOPC Chief Executive Officer Sarah Hirshland, Bullock adapted.

“I went from being a strong advocate for 2030 to be coming completely converted to 2034,” he admitted. “I looked at all the dynamics associated with a better revenue model. And the one thing that was new to me — I said, man, 10 years, that’s a long time. But if we utilize the Games as a catalyst to do good during those 10 years, having 10 years is actually better because we can get a lot more done.

“One of the things I try to do is listen to people and be careful in taking in their input. Which I did, and here we are. We ended up with the right slot, with the right team, with the right time and it feels perfect.”

Bringing Preparation and Certainty

While it felt perfect, it also had to be confirmed by the IOC. For that to be the case, the SLC-Utah bid group focused on certainty — securing government guarantees with the official bid even as the group plans to have the Games be privately funded. Years ahead of the deadline, the bid group secured 21,000 hotel rooms for the 2034 Games and got agreements with all proposed venues for 2034.

The planned $2.83 billion Games operating budget is almost identical to that of 2002, measured in 2034 dollars. A planned $260 million legacy budget will support long-term community sport programs, including the Utah Olympic Legacy Foundation.

And in coming up with the type of proposal that would appeal to the IOC’s desire for each Games to have its legacy, SLC-Utah came up with the Athletes Family Village, which will support athletes’ families near the Athlete Village at the University of Utah, an idea first raised during a meeting between Bullock, Raney-Norman and bid committee member Lindsey Vonn, the four-time Olympian and three-time medalist.

“No one had thought of it,” Vonn said. “That blew my mind and it blew Fraser’s mind. He looked at me and he said, well, we have to do that. And it was instantaneous that everyone said this is an amazing idea. We have to figure out a way to get this done.”

For Vonn, the idea is a personal one: “I love the Olympics,” she said. “My family loves the Olympics. Had my family been able to be in a family village, that would have changed everything. Everything. Most of my family weren’t able to come to most of my Olympics because it was just too challenging. So we are going to change that and we are going to include the families. That for me is a very emotional topic and something that I’m very proud of.”

As the planning and budgeting went on, there was a bit of role reversal that showcased the depth of the relationship between the bid group and IOC. At one point, Bach downplayed the idea of having a dual award for 2030 and 2034. When Bullock emphasized the importance of such a move to the IOC, the committee changed course and approved a dual award for the summer of 2024, formally inviting Salt Lake to targeted dialogue in fall 2023 that all but secured the bid after a formal visit by the Future Host Commission in April.

“It’s so hard to align everything where you’ve got political leadership, public support, everything else,” he said. “Because when you look at Sapporo, you look at Vancouver, you look at Stockholm, they all have wonderful people. But it’s hard to get alignment. And when you’ve got that alignment, you’ve got to make it happen.

“If we had to wait another three years, I don’t know if I could hold it together. We very strongly impressed that upon them. And the good thing is they listened. So we listened to them. They listened to us and we came up with the best answers together.”

A Slight Delay in Approval

So it was onto the IOC Session in Paris and official confirmation for 2034, intentionally scheduled for the morning of Pioneer Day in Utah, the state’s official holiday. The presentations were smooth. The emotions were evident.

“It was very intimidating,” said Vonn — quite a statement given the stakes she competed under as an athlete. “This is probably the biggest speech I’ve ever given in my life and probably one of the most important, if not the most important.”

There was one hitch before the bid’s affirmation, though, as multiple IOC members used the opportunity to lambast the United States Anti-Doping Agency in a show of support for the World Anti-Doping Agency, which came under heavy criticism from U.S. lawmakers in the wake of reports of Chinese swimmers competing at the Tokyo Games in 2021 even after testing positive for doping.

The IOC even put in the host city contract that it can terminate the agreement “in cases where the supreme authority of the World Anti-Doping Agency … is not fully respected or if the application of the world anti-doping code is hindered or undermined.” While a surprise for some, the contract modification and planned show of support for WADA was known by the SLC-Utah bid leaders nearly two weeks prior.

“We understood the concern and provided assurances by letters,” Bullock said. “The entire amendment was just an added clause that we’re very comfortable with.”

After the delay, the actual vote took little time before Bach made Salt Lake’s approval official. The entire mini-drama ended up meaningless because one thing was clear — the IOC wanted (and needed) the Games in Utah. The yes votes for Salt Lake 2034, in fact, were more than the yes votes for the 2030 French bid.

As members from the region, bid leaders, the USOPC and more celebrated in a restaurant in the Palais des Congrès de Paris where the session was held, those who spoke to the gathering including Utah’s governor and Salt Lake City’s mayor needed moments to catch their breath, the enormity of the moment hitting all in attendance.

“There was emotion for all of us,” said Raney-Norman. “We have put our hearts into this. And so, absolutely there were tears.”

Going Forward

The return of the Games to Salt Lake City is not only notable for the Olympics — it was in 2002 that the local organizing committee also organized the Paralympic Winter Games, the first LOC to have done so.

“In Utah, there are opportunities for Paralympic athletes like I haven’t seen anywhere else in the United States,” said Dani Aravich, a two-time Paralympian. “We have some incredible organizations throughout Utah that focus on getting people with disabilities into sports. I know those will just continue to grow as we look towards 2034 and I think Salt Lake will become a place that changes the way we view the Paralympics.”

Partain of Sports Salt Lake also pointed to a decade of future events that will want to be organized in the region. Take, for example, curling, which is scheduled in 2032 to be at the Salt Palace Convention Center, a different venue compared to 2002. That would lend itself to at least one or more events in the next decade to test venue management and logistics.

“There’s events like that, that we know we’re going to have to do things for,” he said. “Then you’ve got USA Hockey, what can we do with them 10 years? U.S. Figure Skating, what can we do with them in the next 10 years? Speed skating is in our backyard, what do we have lined up in the next 10 years? So those are really exciting conversations. And they all want to be here.”

Will things change between now and 2034? Certainly. There is already one venue change from the Paris proposal; Utah Hockey Club owner Ryan Smith says a renovated Delta Center will host ice hockey, moving short track speedskating and figure skating to the Maverik Center in West Valley City.

The composition of a local organizing committee is not fully known, mostly because it will take some time before one is needed. The certainty of having the Games in a decade’s time is countered by the need to maintain local enthusiasm, which has been problematic for other Games hosts.

Those are things that will happen in due course. In the region, the glow of having been awarded the Games still resonates. Bringing the Games back was an Olympic event in and of itself, even for a four-time Olympian such as Raney-Norman.

“One hundred percent it has felt like the journey that you go through as an athlete,” she said that day in Paris, outside of the main session hall. “The work that you put in, the milestones that you hit and all the different markers that you have to continue to hit. To have this moment, it is amazing. It is absolutely the highlight of my Olympic career.”

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000