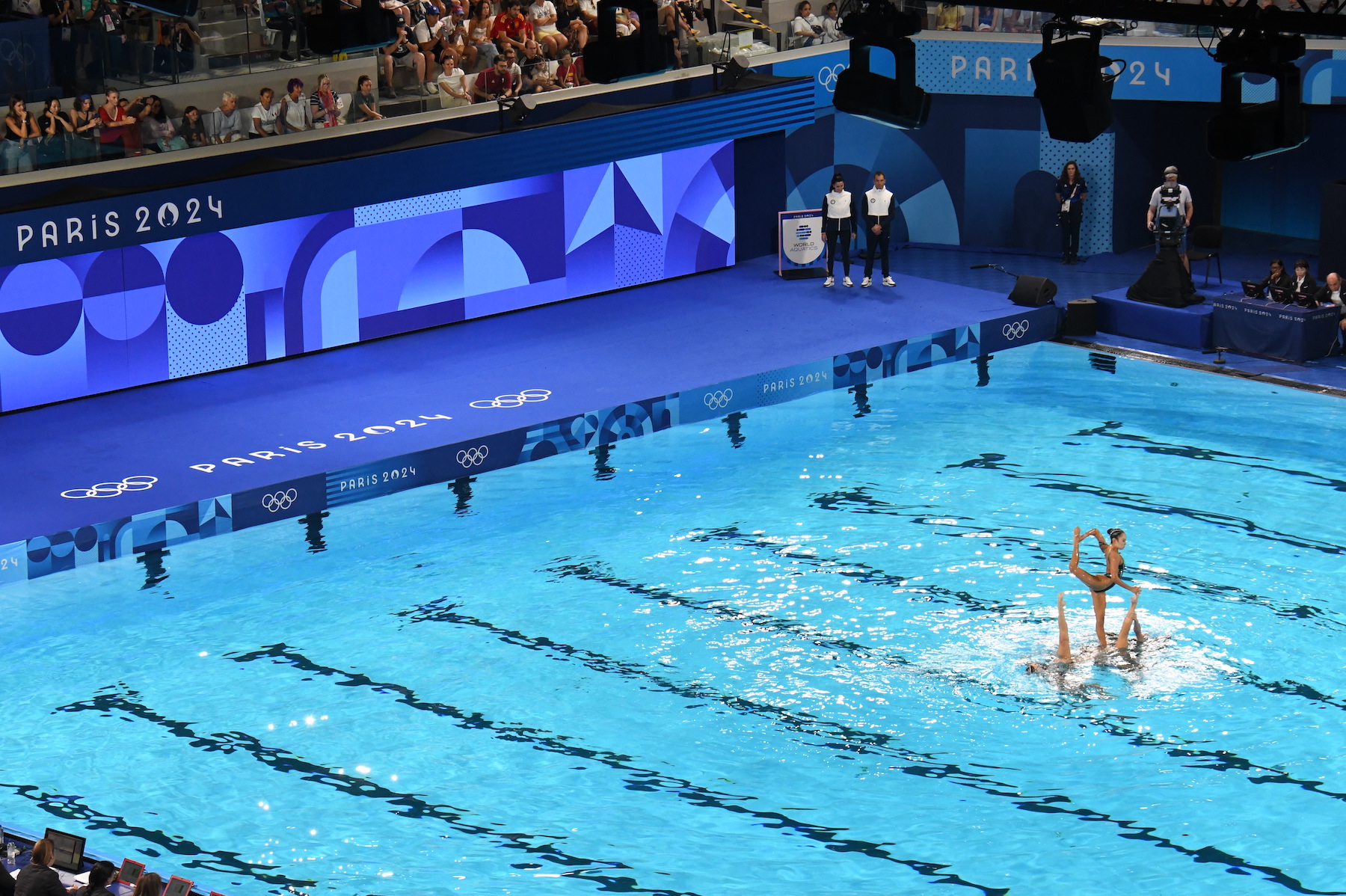

PARIS — In the pantheon of Olympic sports whose athletes get overlooked, artistic swimming may be near the top. Athletes may look flashy in their over-the-top costumes and poses in the water, but make no mistake about what is happening underneath the water to make some of the most dramatic moments of a routine shine.

In some respects, the sport has been overlooked for years in the United State as well. For the past 20 years, artistic swimming has struggled on the Olympic stage, appearing last in the team event at the 2008 Beijing Games and last medaling in that event at the 2004 Athens Games.

That is, until Paris. On Wednesday night, Team USA took home a silver in the team event, finishing behind a heavily favored Chinese squad. The medal is a breakthrough the sport’s athletes and leaders are hoping will last outside of the pool as well.

The U.S. team dominated the early competition of the sport, winning gold in the solo and duet routines when it debuted at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles. But for USA Artistic Swimming, the national governing body’s recent struggles with the team event were linked to challenges in developing a system that enticed athletes to stay in the national team program full time rather than go to college.

In the years since Chief Executive Officer Adam Andrasko took over in 2018 (a move that coincided with the arrival of head coach and four-time Olympic medalist Andrea Fuentes), the national governing body has been working on a slow and steady process to change the culture, right along with an international push to rename the sport from synchronized swimming to artistic swimming.

The new system appears to have worked with the average age of the team increasing along with athlete retention rates. And with the U.S. team back on the podium, many involved with the sport are hoping the turnaround can continue.

“We lost years of momentum and it’s hard to get people to come and join the national team and stick with it when there’s so many unknowns — we’re not getting the results, we’re not getting the funding and the money,” said Anita Alvarez, whose mother also competed in the sport. “Now the U. S. has started to go upward in the ranks, people want to join the team, people want to look up to us and be on this team in the future.”

Andrasko said he expects the moment to continue after the Games on a variety of fronts.

“They showed the world that the sport isn’t just show anymore,” he said of his team. “It is truly athleticism and it’s great things and I think that captivated a lot of people. So now it’s our responsibility as the NGB and the entire sport to build it. I have to use this silver medal not just as a talking point, but as a platform to build up the sport. We want to have bigger events. We want to have more membership.”

Avlarez is a veteran of the sport, becoming only the second American to compete in three Games since she also competes in the duet version of the sport. She and others are hoping the result in Paris can also lead to more financial support, especially in an era where national governing bodies are still being judged on their chance to win medals.

“Hopefully we get more funding and sponsorships and things like that coming in so that people don’t have to question if they can train full time with a national team or go and get a career — this can be the career,” she said. “That’s the hope for the future.”

The effort to get to Paris did not come without challenges. At the 2023 Pan Am Games in Santiago, Chile, where the winner would earn an automatic qualifier to the Olympic Games, the U.S. lost to Mexico by 0.6638 points out of 786 points, a gut punch of a result where the third-place team was 123 points behind. The U.S. had never lost a competition to Mexico before that. But at the final qualification event in Doha, the U.S. placed high enough to earn their spot in Paris.

“It was such a narrow margin,” said Jacklynn Luu of the team’s loss at the Pan Am Games. “It was a huge disappointment for us because we worked so hard to get that qualification, but we knew it wasn’t our last shot. We really used that disappointment to fuel us even more. And the results speak for themselves. In Doha, we became medalists. And here, we’re at the Olympics and we’re silver medalists. So, you know, everything happens for a reason.”

And supporters of the sport are hoping the end result in Paris will spark more interest in the competition in the years to come.

“For a whole decade, we didn’t have a team swimming in the Olympics,” Luu said. “And so to be able to have that impact for the future generation just means so much. I’m thinking about when I was a little kid. There are going to be future small boys and little girls who see this routine that we swam and are going to be so inspired by what we created and what we did out there that they’re going to want to do synchro and just enjoy.”

Andrasko said he is also convinced the performance will pay dividends.

“There’s an absolutely no doubt in my mind that we will see more membership,” he said. “There’s always a bump for every sport coming out of Olympic Games. But because of what we’ve accomplished being on this stage, people seeing it that don’t normally see it — I’m going to start receiving phone calls and emails from moms and dads about where do I send my kid to do this thing?”

And that, he said, may lead to bigger events for host cities in the future.

“We’ll have bigger events because we’ll have more membership,” he said. “But for us as an NGB, it’s about philanthropy. It’s about support sponsorships. It’s about how the (U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee) identifies our sport. And now for the first time in 20 years, we’re not just a medal contender. We’re a medalist.”

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000

Copyright © 2025 by Northstar Travel Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. 301 Route 17 N, Suite 1150, Rutherford, NJ 07070 USA | Telephone: (201) 902-2000